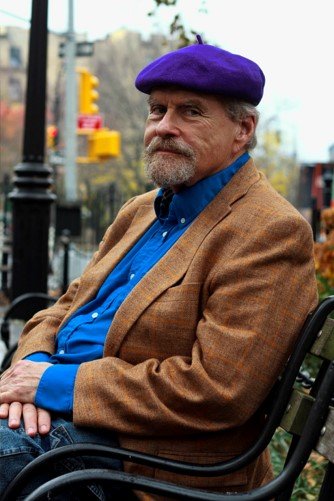

Lawrence Block

Grifter’s Game

Start to Finish: A few weeks

I want to be a writer: 15 Years Old

Experience: Soft-core porn, college newspaper, short stories

Writing Time: A few weeks

Agents Contacted: Already had one

Submission to Publisher: 1960

Year Published: 1961

Time to Sell Novel: I don’t know. A week?

First Novel Agent: Scott Meredith

First Novel Editor: Knox Burger

First Novel Publisher: Fawcett /Gold Medal

Advice to Writers: Write to please yourself.

Website: LawrenceBlock.com

When they’re young, most writers dream of writing the great American novel. Lawrence Block was more pragmatic. He wrote erotica.

It not only paid the bills but forced him to write clean copy for dirty books. He was forced to write clean first drafts because there was so little time for editing if his publisher was to pump out the 15 to 20 soft-core novels he wrote each year to put food on the table. “I never missed any meals,” he says.

Yet only a few years earlier, the brainy kid from Buffalo never dreamed he’d become a writer, much less one who would win numerous Edger, Shamus and Anthony awards during his long career.

“I was 15, and in the eleventh grade,” he says. “I’d always been a reader, but by then I was reading the better American realistic fiction—Steinbeck, Wolfe, Hemingway, O’Hara, Farrell. It hadn’t yet occurred to me that I could attempt to emulate them, but I was beginning to enjoy using words imaginatively, and my English compositions were an outlet. There was one on career plans, and I approached it humorously, enumerating the various occupations I’d considered since age four, when I wanted to be a garbageman. I concluded with: “On rereading this composition, one thing becomes very clear to me—I can never be a writer.”

“I’m not so sure about that!” his teacher, Miss Jepson, wrote in the margin. It would be appropriate to assume she saw something in him that the unaspiring writer didn’t.

“Before that I’d never for a moment considered a career as a writer,” he says, “but from that moment on I never considered anything else.”

Thank you, Miss Jepson, wherever you are.

“My first year at college, I was forever submitting to magazines—mostly poems…I didn’t expect to sell anything, and my non-expectations were fulfilled, but I did manage to amass a slew of rejection slips and paste them on the wall.”

But as every successful writer has done, he persisted and refused to give up.

“The summer before my sophomore year at Antioch, I wrote a story, ‘You Can’t Lose,’ about a young con artist, living by his wits. I stuck it in a drawer, but a couple of months later it occurred to me that it might be a candidate for ‘Manhunt,’ the essential successor to ‘Black Mask.’ I hadn’t even seen a copy of the magazine at the time, but I knew some Evan Hunter stories I admired had been published there, so I looked it up in Writers Market and sent them my story.”

The year 1957 was a turning point for young Block. After his sophomore year, he landed a summer job as an editorial associate at the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, while Meredith was away on vacation. Shortly thereafter, Block found out he had sold “You Can't Lose,” to Manhunt Magazine, only to learn Meredith secretly edited the magazine and had decided to buy Block’s story before they ever met.

“It took a couple of rewrites, but that was my first sale.”

Finally, in 1957, Sidney Meredith, who owned the agency with his brother, signed Block to his first agency contract. Block had just turned 19 and was in good company. During its history the Scott Meredith Literary Agency had represented such literary luminaries as Morris West, Norman Mailer, Arthur C. Clarke and P.G. Wodehouse.

Block initially decided to drop out of college and work at the agency. But after a year he reconsidered and returned to school where he edited the college newspaper, only to drop out for good a year later. He and writer Donald Westlake, who he’d met in 1959, both apprenticed for Midwood Books and Nightstand, publishers of mass market soft-porn paperbacks while Block was still working at the agency.

Block’s first completed novel was written under the pseudonym, Lesley Evans. Strange Are the Way of Love, he says, “Was not erotica. It was a sensitive novel of the lesbian experience, published in 1959 by Crest, then the country’s premier publisher of lesbian fiction. But it was not his first novel to be published. That honor went to Carla, which was published the year before under the pen name Sheldon Lord.

Why erotica?

“It was the writing equivalent of Manhattan real estate. You really couldn’t screw up. We made a lot of wrong decisions,” he told an audience in 2009 at a tribute to his best friend Westlake at Otto Penzer’s Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan. Westlake had died of a heart attack the previous New Year’s Eve. After their initial experience writing erotica, the best friends became cornerstones of their generation in the crime/mystery genre.

“It was an ideal apprenticeship,” Block says. “Midcentury erotica was a wonderfully forgiving medium; so long as you kept the story moving and included sex scenes at regular intervals, the book would be deemed acceptable. No one got rich writing it (although a couple of gentlemen did get rich publishing it), but it meant I could support myself by writing, and if there’s a better way to learn a craft, I don’t know what it might be.”

And it wasn’t pornography as we know it today. This was soft-core, about as tame as sex scenes in today’s typical thriller or crime novel. In Block’s case, there was just more of it.

Before he turned 21, Block was also writing other magazine fiction and crime novels—honing his style, learning the craft—but not under his own name.

He was so prolific, it was no surprise that his first crime novel with the Lawrence Block moniker on the cover, would come quickly. While other writers struggle for years just to find an agent, Block’s move into crime writing sounds almost like an afterthought.

“I started writing a book for either Midwood or Nightstand,” he says. “About two chapters in I thought it might develop into something a cut about either of those markets, that it might in fact work as a crime novel for Gold Medal. I may have shown it to a friend who agreed that it had possibilities. In any event I finished it, and my agent felt it was worth a shot at Gold Medal, and sent it over to Knox Burger, who promptly bought it.”

“If I remember correctly, my original title was ‘The Girl on the Beach.’ Ralph Daigh, the boss at Fawcett, had recently bought a painting of a woman’s face and wanted to put it on the cover of something. So, he changed the title to ‘Mona.’ Somewhere along the way ‘Grifter’s Game’ had been advanced as a possible title, and when Hard Case reprinted the book, that’s what we decided to call it.”

“It wasn’t longer, and I’m not sure it was any deeper, either. There was a little more crime and a little less sex, and it’s possible the writing was on a somewhat higher level,” he says.

“Gold Medal would pay an advance based on the entire press run. If I correctly recall, they paid me $2,500 for Grifter’s Game.

And how well did the novel do?

“[American humorist] Don Marquis said that publishing a volume of verse was like dropping a rose petal into the Grand Canyon and waiting for the echo. A wise man, Don Marquis.”

And why choose and stick with crime fiction all these years rather than some other genre?

“I’ve always liked Stephen King’s counter-question: ‘What makes you assume I had any choice?’”

Does Grifter’s Game hold a special place in his crime-ridden heart?

“It came out sixty years ago, and it shouldn’t astonish you to learn that I don’t spend a tremendous amount of time thinking about it. It is in fact under option for filming, and the option was recently renewed, and whenever that happens, I think of the book, and my thoughts are kind ones, as you might imagine. It’s also in print—the Hard Case paperback, my self-published eBook—and that’s always gratifying.”

The novel went through several reprints before it wound up at Hard Case, including a hardcover edition from Five Star.

The whole process from writing his first novel under his own name to selling it took only a matter of weeks. Right place, right time, right talent—it all came together. When you think of what most famous novelists endure to get published—years of writing, lengthy searches for an agent, and annual anniversaries of rejections before a publisher makes a decision—Block’s effort looks almost like no effort at all. And the fact that he didn’t consider writing as a career until six years before he was published under his own name feels like the gods were on his side.

But if you consider the volume of soft-core erotica he pumped out in just a few years; you begin to understand how his talent was tamed in such a short time.

And look at the breadth of that talent—from his hard-edge Private Investigator Matthew Scudder novels to his lighter Bernie Rhodenbarr gentleman burglar books—it appears Block just needed to discover his own gifts. Obviously, they were there all along and once Miss Jepsen pointed them out, he was all-in. Fortunately for the reading world, he finally discovered his talent (if you can call anything “finally” at the age of 15) and the crime and mystery world has been a more interesting place ever since.