James Patterson

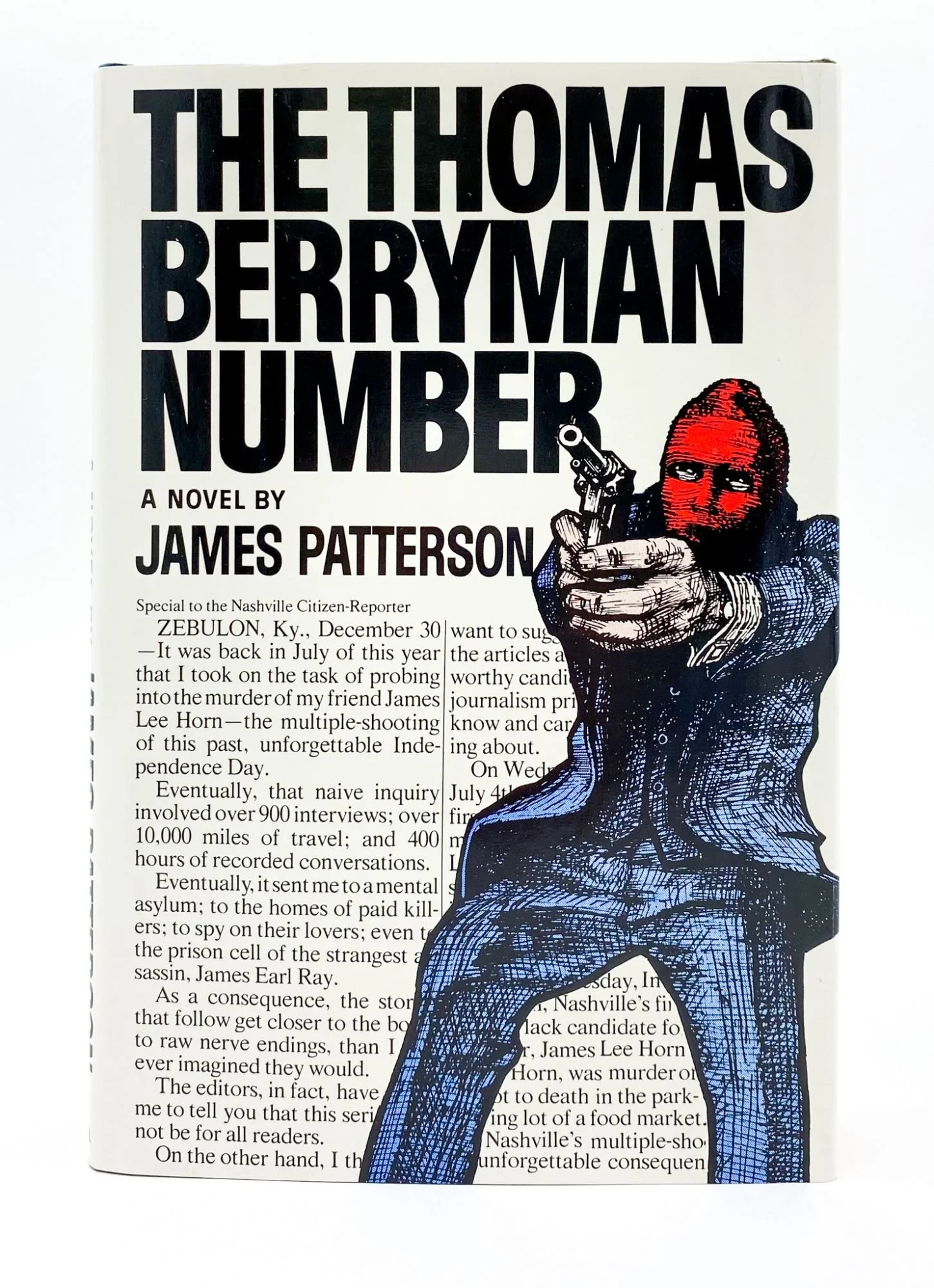

The Thomas Berryman Number

Experience: Advertising Copywriter

Agent Search: One

Publisher Search: 31 rejections

Time to Sell Novel: Six months

First Novel Agent: Francis Greenberg

First Novel Editor: Ned Bradford

First Novel Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Inspiration: Evan S. Connell, Larry McMurtry, Thomas Merton, Philip Roth, Jerzy Kosiński, Thomas F. McGuane III, Lawrence Stern.

Advice to Writers: I don’t give advice. The stuff you nod your head about from my master’s class—you know already. The stuff you shake your head at is what you need to learn.

Website: JamesPatterson.com

James Patterson’s Strength is his Greatest Weakness

It’s almost impossible to imagine.

Between 2010 and 2019, one of every seven crime novels published was by a single author—James Patterson. Working with co-authors, he became a novel writing phenomenon and much more while many literary critics argued his work became much less.

Patterson is well aware of the criticism of his assembly-line style productivity. How can one author, even working with co-authors, churn out dozens of books a year and expect any semblance of quality?

The native New Yorker bonds with his audience and they’re devoted to him. His readers have devoured more than 400 million copies of novels with his name plastered in large type across the cover. He regularly outsells John Grisham, Stephen King and Dan Brown combined.

It’s a fact. The world loves James Patterson and his co-authors even if his critics don’t. Why? Because Patterson understands story.

“My strength is I keep people turning pages, and that’s my greatest weakness because I don’t go in depth,” he says.

He has entire file cabinets full of plot ideas in his office, and more lurking in his head. Patterson never suffers from writer’s block. Ever. His ideas flow like a never-ending stream of consciousness.

When New York Times bestselling thriller author Steve Berry speaks to audiences of aspiring authors about writing, he can’t preach enough about the importance of plot. In a thriller, he says, it trumps character every time. And when another bestselling thriller author, Lee Child, is confronted by the literati about his famed protagonist Jack Reacher’s lack of character depth, he simply responds, “Who’s got the bigger bank account?”

Patterson has overcome the critics because he cares about the reviews that count: his readers. He’s the most prolific author in the world and built one of the biggest author brands ever. But it wasn’t always this way. He once struggled to find his future, especially while in graduate school at Vanderbilt University. At one time Patterson considered trying his hand at writing literature—a far cry from the crime, mystery, and thrillers he writes today.

He wanted to write since he was young, but he had no direction. During his high school senior year, his parents moved from Newburgh, New York to the Boston suburbs. To earn money, he worked the nightshift at nearby McLean mental hospital, which attracted a lot of luminaries like James Taylor, Ray Charles, and poet Robert Lowell. Lowell was a regular and had been there so many times he’d written a poem about his experience, “Waking in the Blue.” Patterson found his way to Lowell’s room often and the poet would read his work to the young man, sometimes twice a day. Patterson soaked up.

In Catholic high school back in New York, “I wasn’t much of a reader…They were giving us a lot of books we didn’t want to read. Suddenly, I’m going into Cambridge and picking up used books for a dime.”

While in college, the novel that moved him most was Mrs. Bridge, a witty story of marriage from a rural Kansas woman’s point of view. Not exactly thriller material, yet it’s author, Evan S. Connell, became one of Patterson’s biggest influences.

“I thought I could write a small literary novel,” he says. But eventually he realized it didn’t appeal to him. “I was a little bit of a literary snob back in college. I didn’t read mysteries. Somewhere along the line I read the Day of the Jackal and The Exorcist. I thought these were kind of cool.”

He was on a path to obtain his PhD and become professor material after graduating summa cum laude with a B.A. in English from Manhattan College. He moved to Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tennessee for grad school, but a college career enhanced by recreational drugs had left him uncertain about his future.

“I was doing too many drugs.” Yet, he notes, “I was doing well in college—mainly A’s—but I needed to clear my head.”

He had always been interested in the writings of Thomas Merton, a trappist monk, theologian, poet, scholar, activist, and bestselling author. So, he decided in February 1970 during his first year at Vandy, to visit the Abbey of Gethsemani, recently Merton’s home south of Louisville, Kentucky, and just up Interstate 65 from Nashville. He wanted to get his head straight and consider the next stage of his life—probably not something unusual for someone who had experienced McLean as an aide.

Patterson spent eleven days that February among the trappist monks thinking about his future and had a long conversation with one of them. “I told him I’ve done a little too much LSD.” The experience, he says, “gave me time to think—think about the whole thing about becoming a writer.”

Days later he walked out of the cloistered environment committed to becoming a novelist.

“Basically, from then and until now, I’ve smoked weed three times and tried coke when I was in the advertising business. And that’s it.”

He returned to Vanderbilt to finish his master’s feature thesis and earn his PhD. But he was quickly motived to end his graduate school experience entirely after earning his master’s. The Vietnam War draft lottery “was the nail in the coffin” for any PhD plans, he says. His high lottery number—265—guaranteed he would not be drafted in 1970 if he were no longer a student, so he quit at the end of spring semester and quickly landed a job as a copywriter with J. Walter Thompson, the iconic advertising agency in New York City.

While working as a copywriter by day, he began writing his first novel. “I didn’t read mysteries, so I didn’t know any of the rules, if there are rules.” His manuscript would eventually be titled The Thomas Berryman Number.

“I had a day job. Got up 5:30 each morning and wrote until 7:30. I was living on the edge of Harlem, wrote in the kitchen, and sat on a metal chair. The kitchen counter was too high for typing and I hurt my back. So, I started writing with a pencil. I’ve been writing with a pencil ever since.”

“What drove me to writing fiction was just people I enjoyed reading. I thought it was presumptuous I could be a writer, but I loved doing it.”

Patterson sent his manuscript directly to William Morrow without the aid of an agent. After five months Morrow rejected it. In all, 31 publishers told him no thanks.

“There were a lot of rejections. Some of them were pleasant— send me your next book—and a lot of them were form.”

Then he heard agent Francis Greenberger was looking for writers for his family literary agency, Sandford J. Greenberger Associates, whose clients included Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Franz Kafka, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. They later represented such luminaries as Nicholas Sparks and Nelson DeMille.

Patterson sent Greenberger his manuscript and two days later received a message to call. Patterson figured it was another rejection. Instead, Greenberger offered to represent him.

Greenberger sent The Thomas Berryman Number to Jay Acton, editor at a small press. Acton worked on the book for a month and then turned it down.

“Don’t worry about it,” Greenberger told Patterson. “I’m going to see this through.” He sent the manuscript with Acton’s edits to Ned Bradford at Little, Brown and Company—the venerated publisher whose clients included Emily Dickinson and J.D. Salinger, and even the works of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. At that time, Bradford was working with Norman Mailer and Herman Wouk, yet after reading Patterson’s debut manuscript was intrigued. Bradford invited him to Little, Brown and Company’s Boston headquarters.

When Patterson arrived, “a woman brought me to the publisher’s library where there was a fire in the fireplace. She brought me tea and coffee on a tray…This was amazing. I’m in this place where all of these famous people had been published. I never forgot that feeling.”

Bradford took him out to lunch and during their meeting, Patterson’s first book blurb arrived from famed crime novelist John D. McDonald.

After several of his publisher’s efforts to design a cover for his novel were rejected, Patterson used his advertising experience to design one himself, which they used. “It actually was a pretty good cover,” he says. The Thomas Berryman Number was published in 1976 while he worked fulltime at J. Walter Thompson. “It was the first publication of anything of mine other than for my college literary magazine.”

Sales were mediocre. He knew better than to give up his day job. In fact, he worked at JWT for another 20 years, eventually rising to CEO—all the while writing novels in his spare time. Finally, turning 50, he resigned to start a fulltime writing career.

As for his novel writing, he says, “I didn’t learn shit at Thompson.” Okay, well maybe something. “The only thing I learned there is there’s an audience.” He said they tested every word that came out of the agency before using it. And that explains a lot about Patterson. He understands the market and the brand for popular crime fiction probably better than any other author.

The Thomas Berryman Number begins in Nashville, Tennessee where Patterson went to grad school. A newspaper reporter tries to hunt down an assassin when a rising politician is murdered. Reporter Ochs Jones links the killing to two other murders and begins to suspect racism is behind it. A manhunt ensues for a dangerous assassin.

Months after publication of The Thomas Berryman Number, Patterson got a call from The Mystery Writers of America telling him his debut novel was nominated for an Edgar Award. Patterson wasn’t familiar with the award and told the caller he couldn’t attend the awards ceremony since it was only a nomination.

“You don’t understand,” the MWA official whispered. “You won.”

He went to the MWA awards ceremony with his parents and picked up the Edgar for Best Debut Novel. At age 27, he was now a published author and an Edgar Award winner. And he was in good company. Robert Parker picked up the Edgar for Best Novel that year.

Since then, Patterson has become a publishing juggernaut and a book publishing philanthropist, pumping millions into the industry. He’s helped independent bookstores stay afloat, given their employees holiday bonuses, and given millions of books to kids and U.S. military personnel in the U.S. and overseas. He has financially supported public school libraries and his and his wife’s alma maters, created teacher scholarships, and has been very public in his support for striking writers in Hollywood.

His success has gone beyond anything he could ever imagine and far beyond the dreams of authors everywhere. His success might be ascribed to his year at Vanderbilt University when Patterson discovered a truism for every aspiring writer: It’s better to talk with a trappist monk about your future than to listen to book critics complain about your past.